Remotes in GitHub

Overview

Teaching: 45 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

How do I share my changes with others on the web?

Objectives

Explain what remote repositories are and why they are useful.

Push to or pull from a remote repository.

Version control really comes into its own when we begin to collaborate with other people. We already have most of the machinery we need to do this; the only thing missing is to copy changes from one repository to another.

Systems like Git allow us to move work between any two repositories. In practice, though, it’s easiest to use one copy as a central hub, and to keep it on the web rather than on someone’s laptop. Most programmers use hosting services like GitHub, Bitbucket or GitLab to hold those main copies; we’ll explore the pros and cons of this in a later episode.

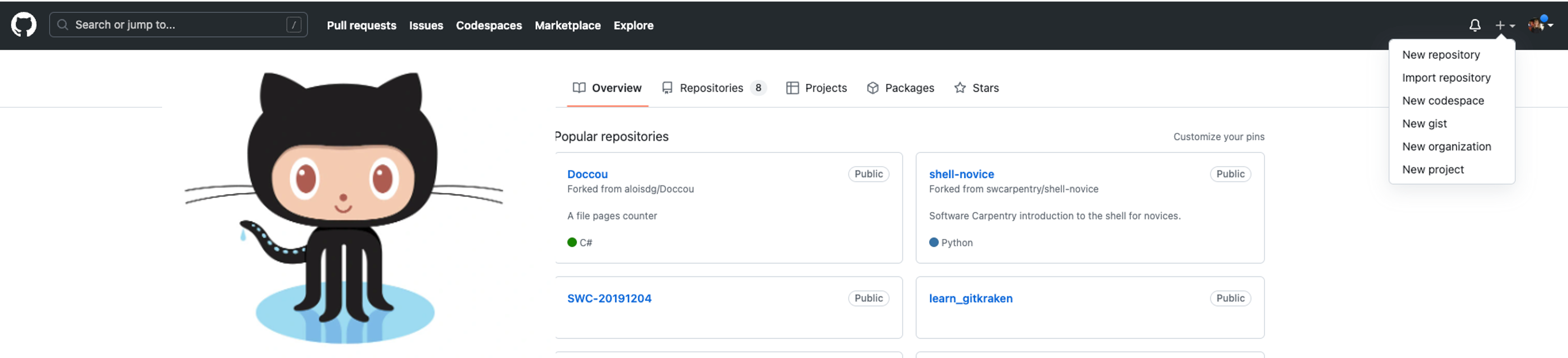

Let’s start by sharing the changes we’ve made to our current project with the

world. Log in to GitHub, then click on the icon in the top right corner to

create a new repository called north-pacific-gyre:

Name your repository “north-pacific-gyre” and then click “Create Repository”.

Note: Since this repository will be connected to a local repository, it needs to be empty. Leave “Initialize this repository with a README” unchecked, and keep “None” as options for both “Add .gitignore” and “Add a license.” See the “GitHub License and README files” exercise below for a full explanation of why the repository needs to be empty.

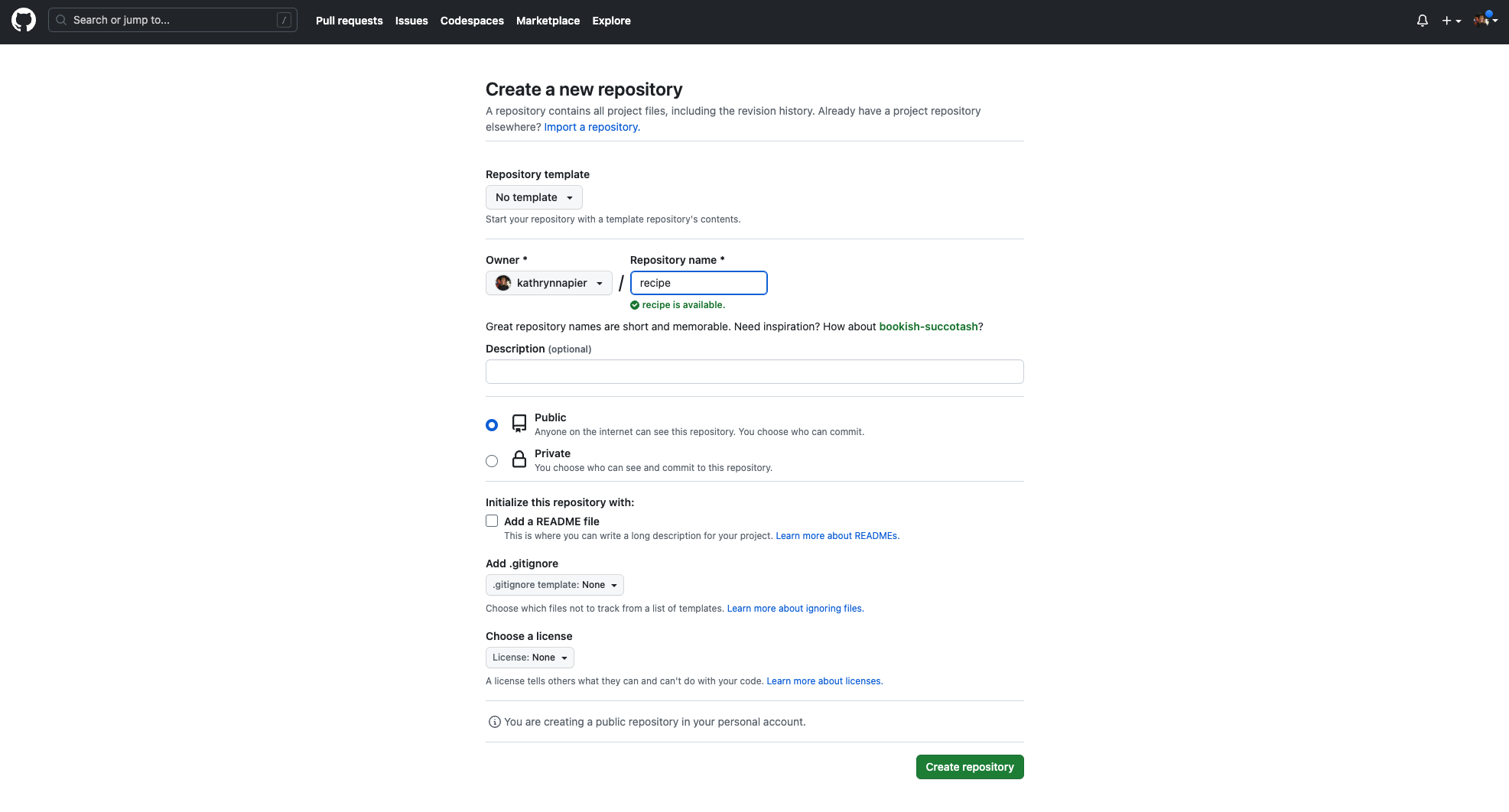

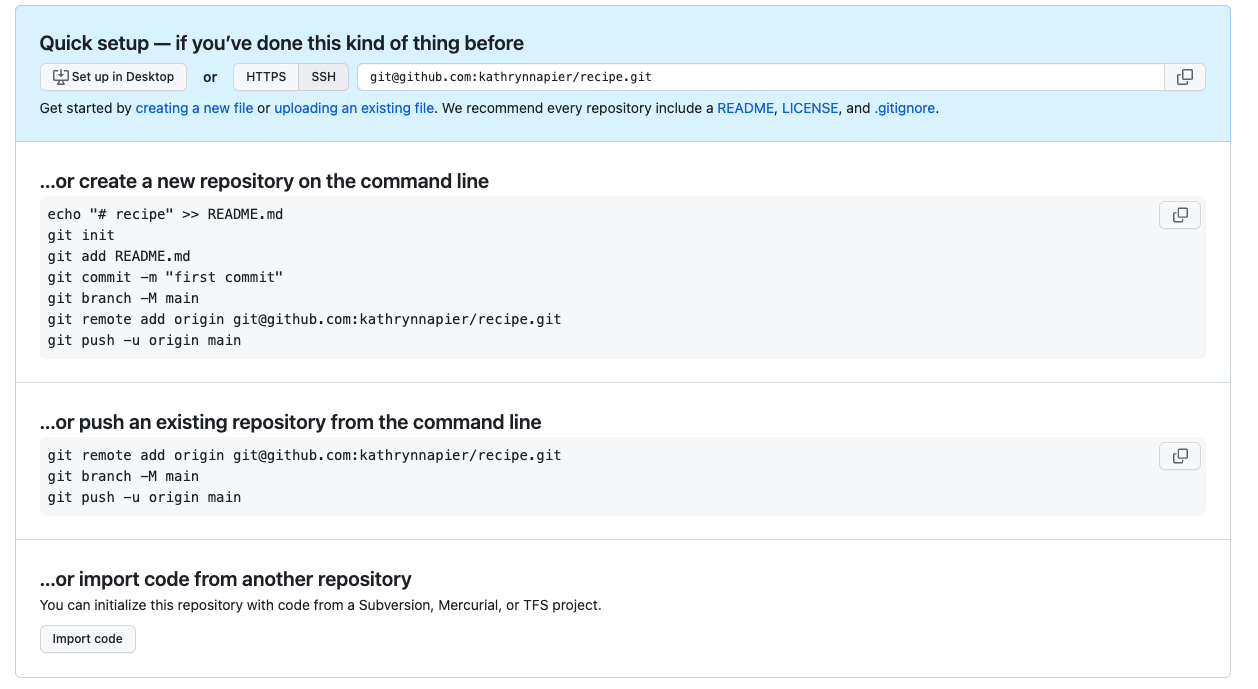

As soon as the repository is created, GitHub displays a page with a URL and some information on how to configure your local repository:

This effectively does the following on GitHub’s servers:

$ mkdir north-pacific-gyre

$ cd north-pacific-gyre

$ git init

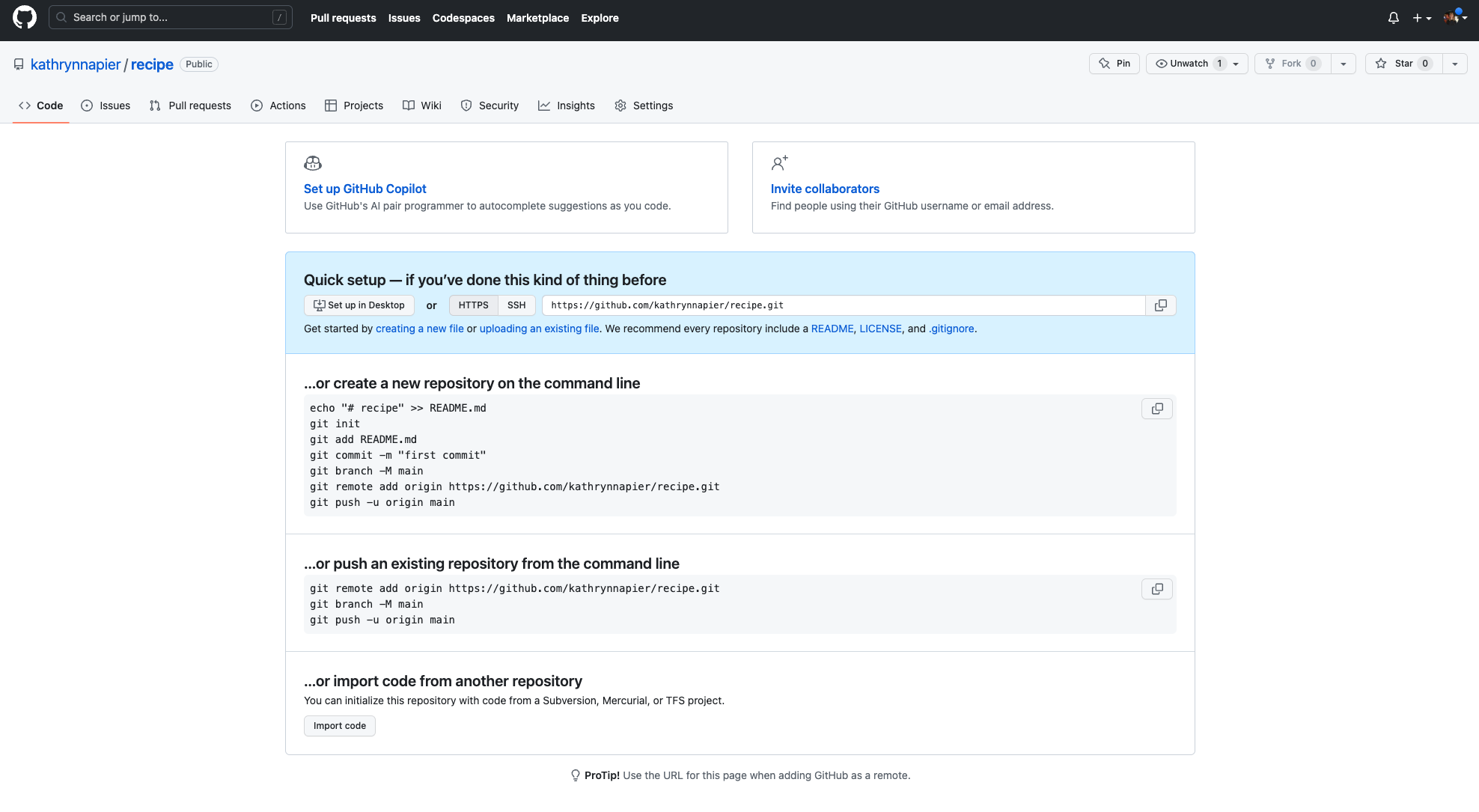

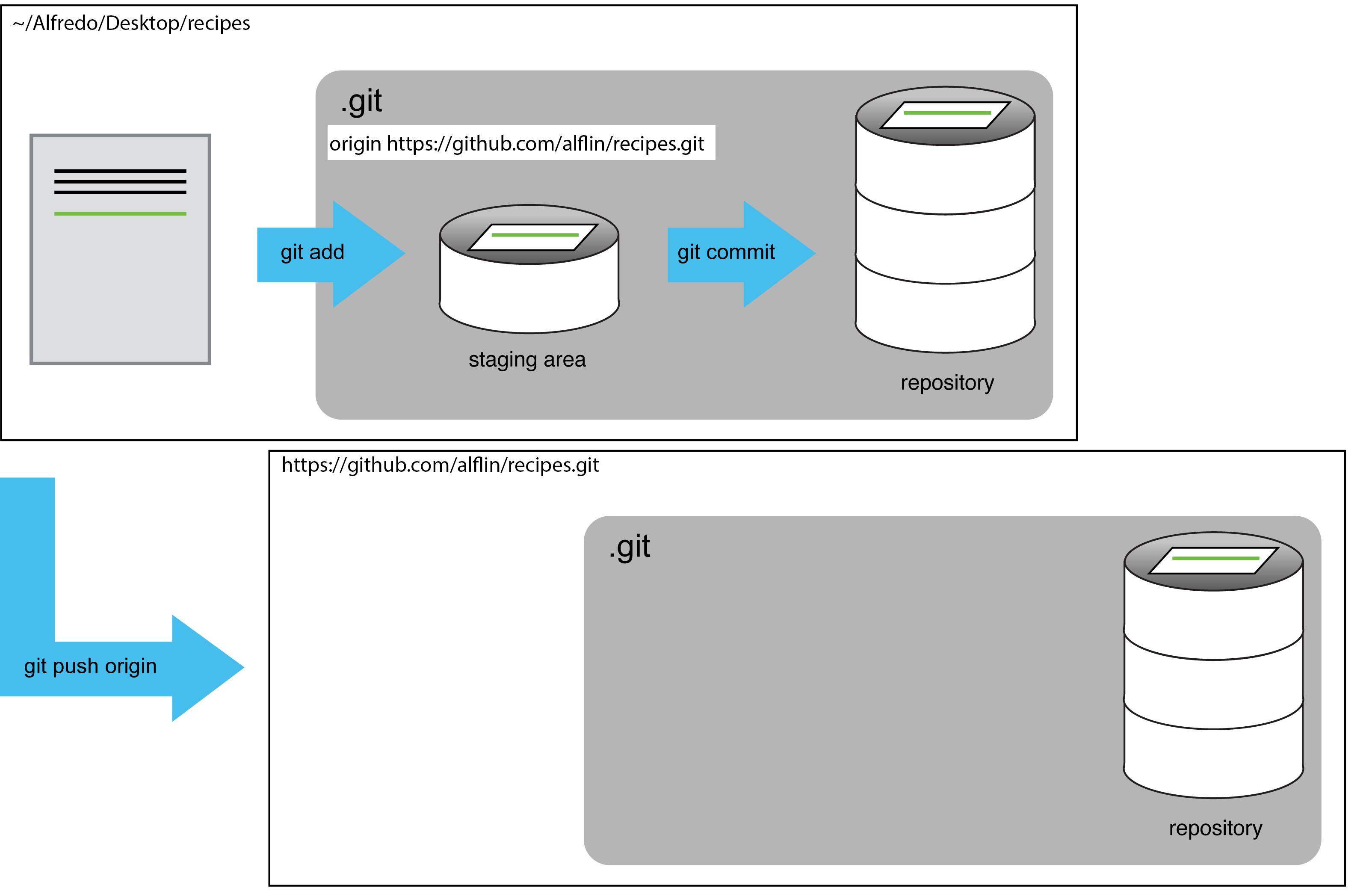

If you remember back to the earlier episode where we added and

committed our earlier work on goostats.sh, we had a diagram of the local repository

which looked like this:

Now that we have two repositories, we need a diagram like this:

Note that our local repository still contains our earlier work on goostats.sh, but the

remote repository on GitHub appears empty as it doesn’t contain any files yet.

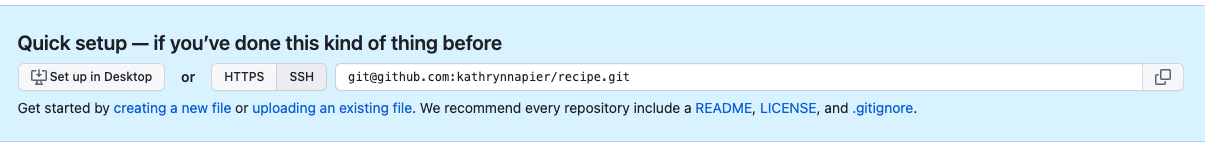

The next step is to connect the two repositories. We do this by making the GitHub repository a remote for the local repository. The home page of the repository on GitHub includes the string we need to identify it:

Click on the ‘SSH’ link to change the protocol from HTTPS to SSH.

HTTPS vs. SSH

We use SSH here because, while it requires some additional configuration, it is a security protocol widely used by many applications. The steps below describe SSH at a minimum level for GitHub. A supplemental episode to this lesson discusses advanced setup and concepts of SSH and key pairs, and other material supplemental to git related SSH.

Copy that URL from the browser, go into the local north-pacific-gyre repository, and run

this command:

$ git remote add origin git@github.com:nelle/north-pacific-gyre.git

Make sure to use the URL for your repository rather than Nelle’s: the only

difference should be your username instead of nelle.

origin is a local name used to refer to the remote repository. It could be called

anything, but origin is a convention that is often used by default in git

and GitHub, so it’s helpful to stick with this unless there’s a reason not to.

We can check that the command has worked by running git remote -v:

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:nelle/north-pacific-gyre.git (push)

origin git@github.com:nelle/north-pacific-gyre.git (fetch)

We’ll discuss remotes in more detail in the next episode, while talking about how they might be used for collaboration.

SSH Background and Setup

Before Nelle can connect to a remote repository, she needs to set up a way for her computer to authenticate with GitHub so it knows it’s him trying to connect to her remote repository.

We are going to set up the method that is commonly used by many different services to authenticate access on the command line. This method is called Secure Shell Protocol (SSH). SSH is a cryptographic network protocol that allows secure communication between computers using an otherwise insecure network.

SSH uses what is called a key pair. This is two keys that work together to validate access. One key is publicly known and called the public key, and the other key called the private key is kept private. Very descriptive names.

You can think of the public key as a padlock, and only you have the key (the private key) to open it. You use the public key where you want a secure method of communication, such as your GitHub account. You give this padlock, or public key, to GitHub and say “lock the communications to my account with this so that only computers that have my private key can unlock communications and send git commands as my GitHub account.”

What we will do now is the minimum required to set up the SSH keys and add the public key to a GitHub account.

Advanced SSH

A supplemental episode in this lesson discusses SSH and key pairs in more depth and detail.

The first thing we are going to do is check if this has already been done on the computer you’re on. Because generally speaking, this setup only needs to happen once and then you can forget about it.

Keeping your keys secure

You shouldn’t really forget about your SSH keys, since they keep your account secure. It’s good practice to audit your secure shell keys every so often. Especially if you are using multiple computers to access your account.

We will run the list command to check what key pairs already exist on your computer.

ls -al ~/.ssh

Your output is going to look a little different depending on whether or not SSH has ever been set up on the computer you are using.

Nelle has not set up SSH on her computer, so her output is

ls: cannot access '/c/Users/Nelle/.ssh': No such file or directory

If SSH has been set up on the computer you’re using, the public and private key pairs will be listed. The file names are either id_ed25519/id_ed25519.pub or id_rsa/id_rsa.pub depending on how the key pairs were set up.

Since they don’t exist on Nelle’s computer, she uses this command to create them:

$ ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "nelle@numa.org"

If you are using a legacy system that doesn’t support the Ed25519 algorithm, use:

$ ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096 -C "your_email@example.com"

Generating public/private ed25519 key pair.

Enter file in which to save the key (/c/Users/Nelle/.ssh/id_ed25519):

We want to use the default file, so just press Enter.

Created directory '/c/Users/Nelle/.ssh'.

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):

Now, it is prompting Nelle for a passphrase. Since she is using her kitchen’s laptop that other people sometimes have access to, she wants to create a passphrase. Be sure to use something memorable or save your passphrase somewhere, as there is no “reset my password” option.

Enter same passphrase again:

After entering the same passphrase a second time, we receive the confirmation

Your identification has been saved in /c/Users/Nelle/.ssh/id_ed25519

Your public key has been saved in /c/Users/Nelle/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

The key fingerprint is:

SHA256:SMSPIStNyA00KPxuYu94KpZgRAYjgt9g4BA4kFy3g1o nelle@numa.org

The key's randomart image is:

+--[ED25519 256]--+

|^B== o. |

|%*=.*.+ |

|+=.E =.+ |

| .=.+.o.. |

|.... . S |

|.+ o |

|+ = |

|.o.o |

|oo+. |

+----[SHA256]-----+

The “identification” is actually the private key. You should never share it. The public key is appropriately named. The “key fingerprint” is a shorter version of a public key.

Now that we have generated the SSH keys, we will find the SSH files when we check.

ls -al ~/.ssh

drwxr-xr-x 1 Nelle 197121 0 Jul 16 14:48 ./

drwxr-xr-x 1 Nelle 197121 0 Jul 16 14:48 ../

-rw-r--r-- 1 Nelle 197121 419 Jul 16 14:48 id_ed25519

-rw-r--r-- 1 Nelle 197121 106 Jul 16 14:48 id_ed25519.pub

Now we run the command to check if GitHub can read our authentication.

ssh -T git@github.com

The authenticity of host 'github.com (192.30.255.112)' can't be established.

RSA key fingerprint is SHA256:nThbg6kXUpJWGl7E1IGOCspRomTxdCARLviKw6E5SY8.

This key is not known by any other names

Are you sure you want to continue connecting (yes/no/[fingerprint])? y

Please type 'yes', 'no' or the fingerprint: yes

Warning: Permanently added 'github.com' (RSA) to the list of known hosts.

git@github.com: Permission denied (publickey).

Right, we forgot that we need to give GitHub our public key!

First, we need to copy the public key. Be sure to include the .pub at the end, otherwise you’re looking at the private key.

cat ~/.ssh/id_ed25519.pub

ssh-ed25519 AAAAC3NzaC1lZDI1NTE5AAAAIDmRA3d51X0uu9wXek559gfn6UFNF69yZjChyBIU2qKI nelle@numa.org

Now, going to GitHub.com, click on your profile icon in the top right corner to get the drop-down menu. Click “Settings,” then on the settings page, click “SSH and GPG keys,” on the left side “Account settings” menu. Click the “New SSH key” button on the right side. Now, you can add the title (Nelle uses the title “Nelle’s Kitchen Laptop” so she can remember where the original key pair files are located), paste your SSH key into the field, and click the “Add SSH key” to complete the setup.

Now that we’ve set that up, let’s check our authentication again from the command line.

$ ssh -T git@github.com

Hi Nelle! You've successfully authenticated, but GitHub does not provide shell access.

Push local changes to a remote

Now that authentication is setup, we can return to the remote. This command will push the changes from our local repository to the repository on GitHub:

$ git push origin main

Since Nelle set up a passphrase, it will prompt him for it. If you completed advanced settings for your authentication, it will not prompt for a passphrase.

Enumerating objects: 16, done.

Counting objects: 100% (16/16), done.

Delta compression using up to 8 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (11/11), done.

Writing objects: 100% (16/16), 1.45 KiB | 372.00 KiB/s, done.

Total 16 (delta 2), reused 0 (delta 0)

remote: Resolving deltas: 100% (2/2), done.

To https://github.com/nelle/north-pacific-gyre.git

* [new branch] main -> main

Proxy

If the network you are connected to uses a proxy, there is a chance that your last command failed with “Could not resolve hostname” as the error message. To solve this issue, you need to tell Git about the proxy:

$ git config --global http.proxy http://user:password@proxy.url $ git config --global https.proxy https://user:password@proxy.urlWhen you connect to another network that doesn’t use a proxy, you will need to tell Git to disable the proxy using:

$ git config --global --unset http.proxy $ git config --global --unset https.proxy

Password Managers

If your operating system has a password manager configured,

git pushwill try to use it when it needs your username and password. For example, this is the default behavior for Git Bash on Windows. If you want to type your username and password at the terminal instead of using a password manager, type:$ unset SSH_ASKPASSin the terminal, before you run

git push. Despite the name, Git usesSSH_ASKPASSfor all credential entry, so you may want to unsetSSH_ASKPASSwhether you are using Git via SSH or https.You may also want to add

unset SSH_ASKPASSat the end of your~/.bashrcto make Git default to using the terminal for usernames and passwords.

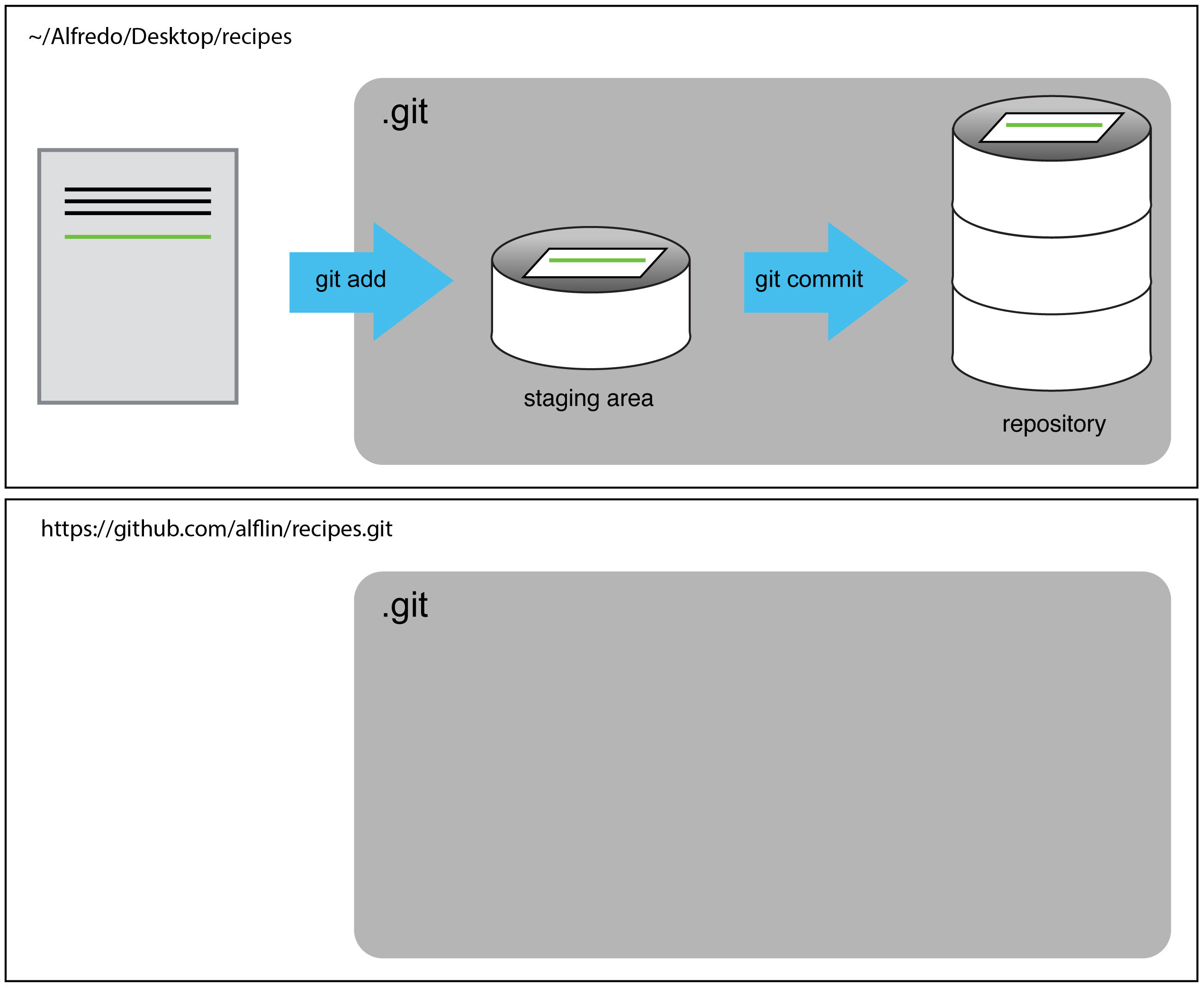

Our local and remote repositories are now in this state:

The ‘-u’ Flag

You may see a

-uoption used withgit pushin some documentation. This option is synonymous with the--set-upstream-tooption for thegit branchcommand, and is used to associate the current branch with a remote branch so that thegit pullcommand can be used without any arguments. To do this, simply usegit push -u origin mainonce the remote has been set up.

We can pull changes from the remote repository to the local one as well:

$ git pull origin main

From https://github.com/nelle/north-pacific-gyre

* branch main -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up-to-date.

Pulling has no effect in this case because the two repositories are already synchronized. If someone else had pushed some changes to the repository on GitHub, though, this command would download them to our local repository.

GitHub GUI

Browse to your

north-pacific-gyrerepository on GitHub. Under the Code tab, find and click on the text that says “XX commits” (where “XX” is some number). Hover over, and click on, the three buttons to the right of each commit. What information can you gather/explore from these buttons? How would you get that same information in the shell?Solution

The left-most button (with the picture of a clipboard) copies the full identifier of the commit to the clipboard. In the shell,

git logwill show you the full commit identifier for each commit.When you click on the middle button, you’ll see all of the changes that were made in that particular commit. Green shaded lines indicate additions and red ones removals. In the shell we can do the same thing with

git diff. In particular,git diff ID1..ID2where ID1 and ID2 are commit identifiers (e.g.git diff a3bf1e5..041e637) will show the differences between those two commits.The right-most button lets you view all of the files in the repository at the time of that commit. To do this in the shell, we’d need to checkout the repository at that particular time. We can do this with

git checkout IDwhere ID is the identifier of the commit we want to look at. If we do this, we need to remember to put the repository back to the right state afterwards!

Uploading files directly in GitHub browser

Github also allows you to skip the command line and upload files directly to your repository without having to leave the browser. There are two options. First you can click the “Upload files” button in the toolbar at the top of the file tree. Or, you can drag and drop files from your desktop onto the file tree. You can read more about this on this GitHub page

GitHub Timestamp

Create a remote repository on GitHub. Push the contents of your local repository to the remote. Make changes to your local repository and push these changes. Go to the repo you just created on GitHub and check the timestamps of the files. How does GitHub record times, and why?

Solution

GitHub displays timestamps in a human readable relative format (i.e. “22 hours ago” or “three weeks ago”). However, if you hover over the timestamp, you can see the exact time at which the last change to the file occurred.

Push vs. Commit

In this episode, we introduced the “git push” command. How is “git push” different from “git commit”?

Solution

When we push changes, we’re interacting with a remote repository to update it with the changes we’ve made locally (often this corresponds to sharing the changes we’ve made with others). Commit only updates your local repository.

Key Points

A local Git repository can be connected to one or more remote repositories.

Use the SSH protocol to connect to remote repositories.

git pushcopies changes from a local repository to a remote repository.

git pullcopies changes from a remote repository to a local repository.